Don’t Panic: The Implications of McGirt v. Oklahoma for the Oil and Gas Industry in Oklahoma

by Stephanie Moser [1]

On July 9, 2020 the United States Supreme Court issued its opinion in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which recognized that the reservation established by Congress for the Creek Nation of Indians has never been disestablished. [2]

The decision, in and of itself, will not change record ownership of the lands within the boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. However, McGirt will result in changes to tribal, state, and federal criminal and civil jurisdiction in the area located within the geographical boundaries of the Tribe’s reservation.

Introduction – The Nature of Tribal Property Rights

The United States Congress has plenary authority over Indian affairs.[3] Although tribes are sovereign entities, the Supreme Court has characterized tribes as “domestic dependent nations” rather than territories or foreign states.[4] The historical foundation for the Court’s definition of the tribal-federal relationship is rooted in the Court’s recognition of the property rights of indigenous tribes and their people, whose rights which were deemed by the Supreme Court to be limited to a possessory interest, incapable of alienation without permission of the United States.[5] Thus, the Supreme Court defined the tribal-federal relationship as a trustor/trustee relationship, akin to that of a ward subject to guardianship.[6] The federal trust obligation to tribes continues to this day.

Prior to the removal of the Five Tribes to Indian Territory, the Supreme Court was called upon to the examine the jurisdictional boundaries of state and tribal governments. In Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832), the United States Supreme Court affirmed one of the foundational principles of federal Indian law: Generally, state law has no force within Indian country.[7] Thus, states are limited in their ability to exercise jurisdiction within the geographical boundaries of a tribe’s “Indian country” as defined by federal law. However, through the passage of time, and shifts in federal Indian policy, Congress has both expanded and limited state jurisdiction in Indian country. In some circumstances, Congress opted to expressly delegate criminal and civil jurisdiction over matters arising within Indian country to states.[8]

Consequently, any legal analysis of whether a state has the power to apply its law within the boundaries of Indian country must begin by identifying the specific statute through which Congress granted that jurisdiction to the state. For example, after Oklahoma statehood, Congress enacted legislation that specifically delegated jurisdiction to the State over some matters involving allotted lands of Five Tribes allottees and their heirs, such as guardianship and probate, quiet title and partition actions, and sales and leasing of restricted Indian lands. By contrast, probate, sales, and leasing of trust lands of tribes[9] located within the State’s geographical boundaries are subject to the exclusive federal jurisdiction of the United States, through the Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs.

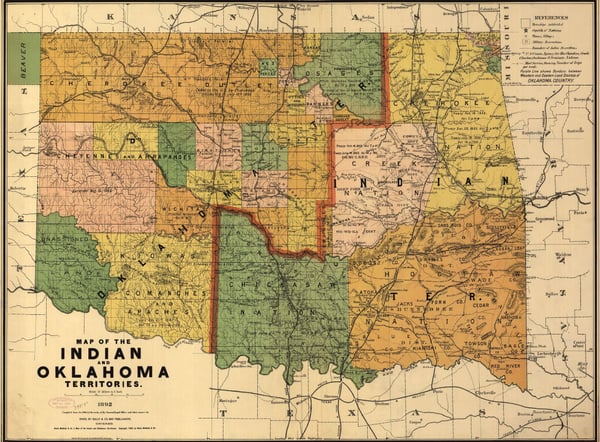

As one of the “Five Civilized Tribes”[10] that were forcibly removed to Indian Territory under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Creek Nation, as a confederacy of tribal towns, executed numerous treaties with the United States governing the terms of their removal to Indian Territory. Article IV of the 1832 Treaty with the Creeks expressly provided that fee simple patents to the Tribe’s lands would be issued to the Tribe.[11] The United States issued a fee patent to the Creek Nation in 1852.[12]

In the years following the removal of the Creek Nation to Indian Territory, Congress initiated a policy of allotment, which began pre-statehood, but wasn’t effected until after statehood. In an attempt to abolish tribal governments, Congress enacted allotment acts to force tribes to divide their communally-owned lands for distribution to individual members of each tribe. Because of the unique nature in which the Creek Nation held title to its lands, the Tribe (along with the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole tribes) was excepted from the provisions of the Dawes Act of 1887.[13] Passage of the Curtis Act in 1898 forced allotment onto the Five Tribes.[14] Due to the passage of time and transfers of tribal lands (voluntarily and involuntarily) into non-tribal ownership, tribal jurisdictional boundaries became disconnected from property boundaries.

McGirt v. Oklahoma: The United States Supreme Court Recognizes the Existence of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation

In McGirt v. Oklahoma, the case at issue involved an appeal by a member of the Seminole Nation who was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison without parole by the State of Oklahoma for crimes of rape, lewd molestation, and forcible sodomy against a minor child.[15] The offenses for which the inmate was convicted occurred within the boundaries of the Creek Nation reservation that had been established by an 1866 treaty with the United States.[16] McGirt’s convictions were for crimes that fell within the category of crimes enumerated in the Major Crimes Act of 1885 (now codified at 18 U.S.C §1153). The Major Crimes Act asserted the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal government over certain criminal offenses committed by Indian perpetrators within “Indian country.” McGirt argued that because his offenses were committed in Indian country, the United States had the exclusive jurisdiction to try his crimes, thereby invalidating the State’s conviction for lack of jurisdiction.

In his Opinion for the majority, Justice Gorsuch applied the reservation disestablishment analysis of Solem v. Bartlett, 465 U.S. 436 (1984) and extensively analyzed the language of the treaties between the United States and the Creek Nation of Indians and relevant congressional legislation to determine whether the boundaries of the Reservation had been disestablished. Finding no language in which Congress expressly disestablished the Reservation, the Court determined that McGirt’s crimes were committed on lands that fell within the definition of “Indian country” in 18 U.S.C. §1153.

In the second paragraph of his opinion, Justice Gorsuch wrote “Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.” [17] At first glance, this opinion seems limited to criminal jurisdiction. However, a closer examination of 18 U.S.C. §1151, which establishes the legal definition of “Indian country” under federal law, reveals the implications of the decision for civil jurisdiction in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation.

Welcome to “Indian Country” - A Primer on 18 U.S.C. §1151

18 U.S.C. §1151, enacted in 1948, codified of the definition of “Indian country” that had been established by prior decisions of the United States Supreme Court.[18] The statute sets out three different categories of lands considered “Indian country”:

(a) all land within the limits of any Indian reservation under the jurisdiction of the United States Government, notwithstanding the issuance of any patent, and, including rights-of-way running through the reservation,

(b) all dependent Indian communities within the borders of the United States whether within the original or subsequently acquired territory thereof, and whether within or without the limits of a state, and

(c) all Indian allotments, the Indian titles to which have not been extinguished, including rights-of-way running through the same.

Of the three categories of Indian country, only the first category under §1151(a) includes lands that were patented in fee. Thus, if lands fall within the definition of “Indian country” as an “Indian reservation” under §1151(a), a tribe may exercise jurisdiction over lands and activities thereon that aren’t restricted Indian lands or lands held in trust for the tribe or its members. As Justice Gorsuch explained:

“Remember, Congress has defined ‘Indian country’ to include ‘all land within the limits of any Indian reservation...notwithstanding the issuance of any patent, and, including any rights-of-way running through the reservation.’ 18 U.S.C. §1151(a). So the relevant statute expressly contemplates private land ownership within reservation boundaries. Nor under the statute’s terms does it matter whether these individual parcels have passed hands to non-Indians.”[19]

Until now, the State of Oklahoma has based its exercise of criminal and civil jurisdiction over the activities of tribal members arising on fee lands on an erroneous assumption that the categories of “Indian country” located within the geographical boundaries of the State have been limited to 1151(b) and 1151(c).

Although the definition of “Indian country” under 18 U.S.C. §1151 was originally enacted for criminal law purposes, the Supreme Court has incorporated the definition of “Indian country” to analyze questions of civil jurisdiction, leaving no doubt about the applicability of the statute to civil jurisdiction over matters tied to the boundaries of Indian country.[20] By recognizing the existence of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation, McGirt implicitly affirms that the entire reservation would fall within the definition of 18 U.S.C. §1151(a), thereby recognizing the existence of various levels of tribal civil jurisdiction over restricted, trust and fee lands throughout the entire reservation which, as Justice Gorsuch noted, includes “most of Tulsa and certain neighboring communities in Northeastern Oklahoma.”[21]

As evidenced by the briefs, Oklahoma’s litigation strategy in McGirt appears to have been partially rooted in policy arguments regarding the civil jurisdictional ramifications due to recognition of the Reservation and application of 18 U.S.C. §1151(a).[22] While the majority opinion is focused on the issue of criminal jurisdiction arising from the application of the Major Crimes Act, Justice Gorsuch addressed, acknowledged, and disposed of the State’s concerns regarding application of the statute to matters of civil jurisdiction:

“Finally, the State worries that our decision will have significant consequences for civil and regulatory law. The only question before us, however, concerns the statutory definition of ‘Indian country’ as it applies in federal criminal law under the MCA, and often nothing requires other civil statutes or regulations to rely on definitions found in the criminal law. Of course, many federal civil laws and regulations do currently borrow from §1151 when defining the scope of Indian country. But it is far from obvious why this collateral drafting choice should be allowed to skew our interpretation of the MCA, or deny its promised benefits of a federal criminal forum to tribal members.”[23]

Thus, the majority opinion appears to be unfazed by potential changes to the landscape of civil jurisdiction resulting from the application of §1151(a) to the Tribe.[24]

As to potential concerns about tribal jurisdiction over non-members in the Reservation, the Supreme Court has already established a body of caselaw that provides a framework for analyzing potential jurisdictional conflicts in Indian country and limits tribal jurisdiction over non-members on lands privately owned by non-members. Because this jurisdictional framework is tied to tribal membership, enforcement can be a logistical challenge. However, these challenges can be resolved.

The Boundaries of Tribal, State, and Federal Jurisdiction in Indian Country

At any given time in the United States, we are subject to the jurisdiction of multiple governmental entities, often concurrently. Crossing jurisdictional boundaries is such a common and unremarkable experience that it often goes unnoticed when traveling. For example, as many Oklahoma college students and college football fans can attest, travel to the Cotton Bowl at the Texas State Fairgrounds for the annual OU-Texas game results in Oklahomans becoming subject to the jurisdiction of a “foreign” government, namely the State of Texas. Outside of Indian country, any Oklahoman who files a tax return or pays sales taxes on groceries will experience the effects of concurrent jurisdiction between federal, state, county, and municipal governments. Resolution of jurisdictional conflicts is so routine in our legal system that conflicts between federal and state criminal jurisdiction are a common trope used in television crime dramas and action movies.[25] Tribal, state, and federal courts are regularly tasked with adjudicating and resolving jurisdictional conflicts.

As Justice Gorsuch recognized, “With the passage of time, Oklahoma and its Tribes have proven they can work successfully together as partners.”[26] The majority opinion cited numerous examples of intergovernmental agreements between tribes in Oklahoma (including the Muscogee (Creek) Nation) and the State of Oklahoma relating to “taxation, law enforcement, vehicle registration, hunting, and fishing, and countless other fine regulatory questions.”[27] Cross-deputization agreements, memoranda of understanding, and tribal-state compacts governing jurisdiction over activities of both members and non-members on lands located within Indian country, offer examples of how tribes and the State of Oklahoma regularly work together to resolve potential jurisdictional conflicts. Further, the State of Oklahoma requires its district courts to grant full faith and credit to judgments rendered in any tribal court that grants reciprocity to the State, thereby allowing judgements to be given full force and effect across jurisdictional lines.[28]

As to activities within Indian country involving individual non-members and entities owned by non-members, the United States Supreme Court has addressed the limitations of tribal, state, and federal civil jurisdiction over tribal members and non-members within and outside of Indian country. Generally, the analysis of whether tribal jurisdiction extends to non-members and non-tribal entities considers not only the location of the event that gave rise to the litigation, but whether or not the parties involved were tribal entities or members of the tribe.

The Montana Exceptions: The Supreme Court Curtails Tribal Exercise of Jurisdiction over Non-Members in Indian Country

In Montana v. United States, the United States Supreme Court addressed the issue of whether the Crow Tribe of Montana could exercise civil jurisdiction through regulation of hunting and fishing on lands that were located within the boundaries of the reservation, but owned in fee by a non-member.[29] The case established the general rule that a tribe’s exercise of civil jurisdiction does not extend to non-Indians within the reservation, with two exceptions: A tribe retains its inherent power to exercise some forms of civil jurisdiction (e.g., taxation and licensing) over non-Indians on fee lands within its reservation over (1) conduct of nonmembers “who enter consensual relationships with the tribe or its members, through commercial dealing, contracts, leases, or other arrangements” and; (2) “the conduct of non-Indians on fee lands within its reservation when that conduct threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe.”[30]

While the first Montana exception appears straightforward, the second Montana exception is more unclear. In Nevada v. Hicks, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of whether the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Indiana Tribal Court had the jurisdiction to adjudicate a civil rights action by a tribal member against a non-Indian game warden for the State of Nevada, who executed an off-reservation search warrant of the tribal member’s property held in fee, but located on the reservation. Holding that the tribal court did not have jurisdiction under the second Montana exception, the Supreme Court added a caveat that “Tribal assertion of regulatory authority over nonmembers must be connected to that right of the Indians to make their own laws and be governed by them.”[31]

The more recent trend in the Court’s decisions has been to construe the Montana exceptions narrowly. For example, in Atkinson Trading Co. v. Shirley, the Court rejected application of the Navajo Nation’s hotel occupancy tax on the non-tribal operator of a hotel located on fee lands within the Navajo Nation Reservation.[32] Because the operator was licensed to operate by the Navajo Nation, the Tribe argued that the first Montana exception applied due to the operator’s consensual relationship with the Tribe resulting from the application for the license, and alternatively, that the second Montana exception permitted the application of the tax as necessary to maintaining the political integrity of the Tribe. The Court rejected the application of both Montana exceptions, distinguishing a previous line of cases permitting tribes to tax non-members.[33]

In Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land & Cattle Co., the Court held that the Cheyenne River Sioux Indian Tribal Court lacked jurisdiction to adjudicate a discrimination claim between an Indian couple and a non-Indian bank arising from the bank’s sale of fee land within the Tribe’s reservation to non-Indians instead of the couple.[34] In his opinion for the majority, Justice Roberts interpreted the exception narrowly, rejecting the argument that Montana permits a tribe to regulate the sale of fee lands within the reservation by distinguishing the sale of land between non-members from conduct on the land by non-members.[35] Noting that tribal governments exist outside of the scope of the U.S. Constitution and the inapplicability of the Bill of Rights, the Court signaled its skepticism at the prospect of a tribe “subjecting nonmembers to tribal regulatory authority without commensurate consent.”[36] The Court noted that because nonmembers have no say in tribal government or the laws and regulations governing activity in Indian country, “those laws and regulations may be fairly imposed on nonmembers only if the nonmember has consented, either expressly or by his actions.”[37]

By limiting jurisdiction of tribal courts over non-Indians and non-members of a tribe, the Montana line of cases refutes the State of Oklahoma’s argument in McGirt that recognition of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation will lead to chaos in civil jurisdiction. Further, as to the Five Tribes, Congress specifically conveyed civil jurisdiction to the State in certain adjudicatory and regulatory matters, including oil and gas conservation issues.

What is the Scope of Oklahoma Corporation Commission Jurisdiction in Indian Country?

As noted earlier, although Congress has plenary authority over Indian affairs, it has, on occasion, delegated jurisdiction to states. In Section 11 of the Act of August 4, 1947 (61 Stat. 731), also known as the Stigler Act, Congress provided that “all restricted lands of the Five Civilized Tribes are hereby made subject to all oil and gas conservation laws of the State of Oklahoma; Provided, that no order of the Corporation Commission affecting restricted Indian land shall be valid as to such land until submitted to and approved by the Secretary of the Interior or his duly authorized representative.” Both the plain text of the Act and legislative hearings on H.R. 3173 made it clear that Congress considered the State’s jurisdiction as concurrent with the United States, rather than exclusive, as the validity of OCC orders was conditioned on approval of the Secretary of the Interior.[38] Further, the federal government maintains concurrent jurisdiction to this day, as oil and gas leases can still be submitted for approval directly to the United States Department of the Interior under the procedure set forth at 25 C.F.R. Part 213.

The plain language of Section 11, in which the federal government delegates regulatory authority over restricted Indian lands to the State by subjecting those lands to “oil and gas conservation laws,” appears notably broad. In Currey v. Corporation Commission v. Oklahoma, lessees of leases covering restricted Choctaw lands attempted to argue that the Oklahoma Corporation Commission lacked jurisdiction to order the replugging of abandoned wells that were purging salt water.[39] One of the arguments advanced by the Appellants was that the federal government had exclusive jurisdiction to order reworking or replugging of the wells, citing Article 1, Section 3 of the Oklahoma Constitution, in which the State of Oklahoma disclaimed “all of its right and title in or to any unappropriated public lands lying within said limits owned or held by any Indian, tribe, or nation; and that until the title to any such public land shall have been extinguished by the United States, the same shall be and remain subject to the jurisdiction, disposal, and control of the United States.”

Citing Section 11 of the Stigler Act, the Court rejected the Appellants’ arguments, stating that Section 11 “specifically withdraws Congress from preemption in the field of oil and gas conservation and thereby enlarged the sovereignty of Oklahoma to that extent.”[40] In its analysis interpreting the effect of Article 1, Section 3 of the Oklahoma Constitution, the Court also recognized an important distinction between title to lands, and jurisdiction over lands and activities thereon: “Oklahoma's disclaimer of right and title to Indian lands is a disclaimer of proprietary rather than governmental interests. The State may well waive its claim to any right or title to the lands and still have all of its political or police power with respect to the actions of the people on those lands, as long as that does not affect the title to the land.” [41]

It should be noted that this decision did not state whether the replugging order that was the subject of the dispute had been submitted to the United States Department of the Interior for approval in accordance with the plain language of the statute. However, on appeal, the United States Supreme Court denied certiorari in the matter.[42]

As to restricted lands, the issue of Oklahoma Corporation Commission regulatory authority over operations on Five Tribes restricted lands appears (relatively) settled. However, lands within the Muscogee (Creek) Nation are not limited to restricted lands and fee lands; the United States also holds lands in trust for the Tribe and its members.[43] For title purposes, the distinction is not merely academic.

Tribal and State Taxation of Oil and Gas

As to civil jurisdiction, one of the biggest ramifications of McGirt is likely to occur in the area of taxation. Like state governments, many tribes are heavily reliant upon the revenue generated by oil and gas production and severance taxes to fund essential government programs and services.

In absent of express federal statutory authority, “Indian tribes and individuals generally are exempt from state taxation within their own territory.”[44] However, Section 3 of the Act of May 10, 1928 specifically stated that “all minerals, including oil and gas, produced on or after April 26, 1931, from restricted allotted lands of members of the Five Civilized Tries in Oklahoma, or from inherited restricted lands of full-blood Indian heirs or devisees of such lands” to “all State and Federal taxes of every kind and character the same as those produced from lands owned by other citizens of the State of Oklahoma.”

Lands acquired and held in trust by the United States for the benefit of a tribe or its matters under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act are a different matter entirely. Although the Act expressly authorizes Oklahoma to collect gross production taxes on lands acquired in trust by the United States for the benefit of a tribe, the lands “shall be free from any and all taxes” except for a GPT “not in excess of the rate applied to production from lands in private ownership.”[45]

Even in instances in which a state lacks express federal authority to levy taxes within Indian country, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld a state’s authority to tax oil and gas produced on lands within Indian country when the incidence of the tax falls upon non-Indian lessees, even when the tribes themselves are lessors.[46] However, numerous logistical problems arise when a state attempts to levy taxes within Indian country. Tribal sovereign immunity makes it nearly impossible for a state to enforce collections, at least against a tribe. Further, for taxes on retail items such as alcohol and tobacco, determining membership on a transaction-by-transaction basis is impractical for most retailers. Consequently, tribes and states have turned to negotiation of tribal-state compacts to resolve the taxation impasse within Indian country, sometimes to the chagrin of non-Indian retailers who operate competing businesses in neighboring jurisdictions who are subject to higher tax rates.[47]

For oil and gas companies doing business in Indian country, the biggest shift for them may lie in the area of tribal taxation. As to tribal authority to levy taxes on oil and gas, including severance taxes, in Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, the Court upheld tribes’ inherent authority to tax non-Indians doing business on the reservation as “a fundamental attribute of sovereignty” enabling a tribe to fund its governmental services.[48] However, the Court did also recognize that “the Tribe’s authority to tax nonmembers is subject to constraints not imposed on other governmental entities: the Federal Government can take away this power...”[49] Thereafter, in Kerr-McGee Corp. v. Navajo Tribe of Indians, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld tribal ordinances imposing possessory interest taxes and business activity taxes applicable to both Navajo and non-Indian businesses without requirement of approval of the Secretary of the Interior.[50] Although neither of these decisions were explicitly limited to the trust lands that were leased, subsequent decisions have relied upon the occurrence of the activities on trust lands (and arguing that the incidence of the tax fell on third party non-members) to utilize the Montana exceptions to distinguish Merrion.[51]

As to regulation of non-member activity on fee lands within the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation, it remains to be seen whether federal courts will limit the Tribe’s jurisdiction under the outlier cases under the Montana exceptions, or whether courts will uphold taxation of natural resources from non-members on fee lands within the Reservation under the Merrion line of cases. Regardless, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation includes both restricted lands and lands held in trust by the United States for the Tribe and its members.

Further, Oklahoma oil and gas taxation and regulatory authority over the Nation’s oil and gas resources does not reach all lands within the Reservation. Even so, it is clear that the existence of state taxation does not, in and of itself, preclude the Tribe from levying its own taxes. The decision as to whether to use oil and gas taxes to fund tribal government lies squarely with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and its citizens. Unlike local governments in the State, the Tribe is not subject to control or preemption by the State legislature absent express federal authority to do so. Thus, energy companies who fail to develop tribal partnerships will be left behind. The industry cannot afford to alienate the Nation or its allies.

Tribal Water Rights and Environmental Regulation

In the interest of brevity, the topic of tribal water rights and environmental regulation is too large of a matter to adequately address in this medium.[52] To roughly summarize: Because the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s title is rooted in fee simple title obtained through treaty rights, the Tribe may be able to claim water rights within its boundaries under the 1866 under the “Five Tribes Water Doctrine.”[53] The recognition of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation could add an additional basis for the Tribe’s claim to reserved water rights under the Winters doctrine.[54] That could be significant, because the Supreme Court has held that implied use of groundwater falls within the existing canon of reserved water rights doctrine.[55] Federal courts could be called upon to adjudicate the issue of whether the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s ownership of property rights in water carries implied rights to quality for the use of the water for its intended purposes.[56]

Ownership of water rights also has the potential to effect analysis of whether the Muscogee (Creek) Nation has the power to regulate non-member activities pertaining to ancillary use of the Tribe’s water within the Reservation. In Montana, the Crow Tribe of Montana asserted title to the riverbed of Big Horn River, and argued that their title to the riverbed justified their claim to regulate the hunting and fishing of nonmembers within its reservation.[57] Ultimately, the Court held that title to the riverbed was held by the State of Montana, rather than the Crow Tribe.[58] Because the Crow Tribe cited Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma,[59] the Court examined the history and treaty rights of the Cherokee Nation and the Choctaw Nation’s to compare the Tribes’ claim to title to the riverbed of the Arkansas River with the Crow Tribe’s claim to the riverbed of the Big Horn River.[60] Because the scope of Montana concerned non-member activities on non-Indian fee lands, by distinguishing other Five Tribes’ ownership of the riverbed, the Court opens a door to the possibility that the Five Tribes could rely upon their property rights in the waterways and riverbeds to regulate non-member activity related to those waters within each tribe’s respective Indian country without being bound by the Court’s narrow construction of the Montana exceptions.[61] Even if that door is shut, water quality and preservation of the wildlife connected to the rivers, lakes, and other bodies of water within the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation in which the Tribe has property rights would appear to fall squarely within the second Montana exception, even if that exception is tightly construed.

As to the rights of the Tribe to administer federal environmental protection programs under the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the Clean Air Act within the Reservation, the Tribe would be much more constrained by federal legislation. Tribes are eligible to apply to the Environmental Protection Agency for Treatment as a State (TAS) status in order to obtain primacy for administration of EPA programs. It is also well established that tribes who obtain TAS status to administer programs under the Clean Water Act have the power to set water quality standards that are more stringent that those of the state.[62] However, since 2005, tribal-state cooperative agreements have been required as a pre-condition for the EPA to grant TAS status to Oklahoma tribes.[63]

Conclusion

The recognition of the existence of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation in McGirt may be initially unsettling for those in the State of Oklahoma who live, travel, and conduct business within the boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. It will take time (and possibly, litigation) to fully determine the implications of the decision for civil jurisdiction in the Reservation. However, tribal, state, and federal governments have many legal tools at their disposal to determine their respective jurisdictional boundaries, and provide those who do business in Indian country with more certainty regarding effects of jurisdictional changes on their boundaries.

What is more certain is this: In a state that includes jurisdictions of thirty-nine federally-recognized tribes, the energy industry cannot afford to exclude tribal governments. As sovereign entities with independent economies, tribes wield significant economic power in the State of Oklahoma. For companies in the energy sector who have not yet established existing partnerships with tribes and tribal economic development authorities, McGirt is a reminder that now, more than ever, it is crucial to develop and strengthen relationships with tribal governments.

[1] Stephanie Moser Goins is a Senior Attorney with Ball Morse Lowe PLLC. Specializing in federal Indian law and oil and gas title, she is licensed to practice before the courts of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the United States Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, the United States District Courts in the Western, Northern, and Eastern Districts of Oklahoma, and the States of Oklahoma and Ohio.

[2] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 1.

[3] Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553, 565-66 (1903).

[4] Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1, 33 (1831).

[5] Johnson v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. 543 (1823).

[6] Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1, 26-27 (1831).

[7] Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832).

[8] See, e.g., Pub. L. No. 83-280, 67 Stat. 588 (1953).

[9] Five Tribes lands are not limited to restricted lands. Their lands include also include lands held in trust by the United States for tribes and their members.

[10] The Five Tribes are the Cherokee Nation, the Chickasaw Nation, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma.

[11] Treaty with the Creeks, March 24, 1832, 7 Stat. 366

[12] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 4-5, citing Woodward v. De Graffenreid, 238 U.S. 284, 293-94 (1915).

[13] Muscogee (Creek) Nation v. Hodel, 851 F.2d 1439, 1441 (D.C. Cir. 1988).

[14] Id.

[15] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 2; Resp. Br. at 4.

[16] Pet. Br. at 16.

[17] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 1.

[18] See Donnely v. United States, 228 U.S. 243 (1913) (holding that lands in California to which aboriginal title to tribal lands had been extinguished, but located within a reservation created by Executive Order after statehood were considered Indian country); United States v. Sandoval, 231 U.S. 28 (1913) (holding that dependent Indian communities, such as lands held in fee simple by the Pueblo Indians in New Mexico, were considered Indian country); United States v. Pelican, 232 U.S. 442 (1913) (holding that trust allotments were considered Indian country); and United States v. McGowan, 302 U.S. 535 (1938) (holding that trust lands in Nevada, purchased post-statehood by the federal government for the Reno Indian Colony, were considered Indian country).

[19] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 10.

[20] DeCoteau v. District County Court for the Tenth Judicial District, 420 U.S. 425, 427 (1974), n. 2. (“While § 1151 is concerned, on its face, only with criminal jurisdiction, the Court has recognized that it generally applies as well to questions of civil jurisdiction); Pittsburg & Midway Coal Mining Co., v. Watchman, 52 F.3d 1531, 1540 (1995).

[21] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 37.

[22] Resp. Br. at 43-44 (“Reversal would force a sea-change in the balance of federal, state, and tribal authority in eastern Oklahoma.” Citing numerous federal statutes, the State’s brief argued that “On the civil side, effects will extend from taxation to family law.”)

[23] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 39-40.

[24] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 40 (“Of course, many federal civil laws and regulations do currently borrow from §1151 when defining the scope of Indian country. But it is far from obvious why this collateral drafting choice should be allowed to skew our interpretation of the MCA, or deny its promised benefits of a federal criminal forum to tribal members.”

[25] See, e.g., “Die Hard,” a popular 1988 Christmas action film in which a major plot point revolves around villain Hans Gruber’s manipulation of the tactics of federal agents, who show up to commandeer jurisdiction from the LAPD over the incident at Nakatomi Plaza. Federal jurisdiction was presumably based on activities under federal terrorism statutes, even though Hans Gruber turned out to be a garden variety robber.

[26] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ____(2020), slip op. at 41.

[27] Id.

[28] 12 O.S. §728-728; Okla. Dist. Ct. R. 30(B).

[29] Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981)

[30] Id. at 565-66.

[31] Nevada v. Hicks, 533 U.S. 353, 361 (2001).

[32] Atkinson Trading Co. v. Shirley, 532 U.S. 645 (2001).

[33] Id. at 650-53.

[34] Plains Commerce Bank v. Long Family Land & Cattle Co., 554 U.S. 316 (2008),

[35] Id. at 340.

[36] Id. at 337. But see provisions of the Indian Civil Rights Act at 25 U.S.C.§ 1302(a)(8), prohibiting any tribe from denying “to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of its laws or deprive any person of liberty or property without due process of law.”

[37] Id.

[38] Restrictions Applicable to Indians of the Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma, and For Other Purposes, 1947: Hearings on H.R. 3173 and H.R. 149 Before the Subcomm. on Indian Affairs of the House Comm. on Public Lands, 80th Cong., 1st Sess. (1947) at 38.

[39] Curry v. Corporation Commission v. Oklahoma, 1979 OK 89, 617 P.2d 177 (Okla. 1979). Although the Stigler Act granted Oklahoma state courts with jurisdiction to approve leases covering restricted Indian lands, the leases in question had been approved by the United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs. The decision does not state why the leases were approved by the BIA rather than the state court. Although records of the OCC indicate that the wells were not spud until the mid-50’s, it is possible that the leases were taken prior to the enactment of the Stigler Act in 1947. Regardless, the Stigler Act does not prohibit a lessee from seeking approval of leases through the BIA procedure set forth at 25 CFR Part 213.

[40] Id. at ¶ 16, 180.

[41] Id.

[42] Currey v. Corporation Commission v. Oklahoma, 452 U.S. 938 (1981)

[43] In 2013, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation enacted NCA 13-266, which established the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Oil and Gas Department. The Department’s duties including monitoring of lease compliance, production reporting, damage assessments, lease negotiations, payment of royalties, and “other matters that relate to the harvesting of Oils and Gas from lands under the Jurisdiction of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.” Id.; NCA 14-177. The law defines “Oil and Gas Activities” as “any activity of a person within the Nation that constitutes or materially assists:

1. The exploration for, development, production, treatment, processing, refining, transportation, sale of oil, natural gas or other Hydrocarbon Materials.

2. The Manufacturing of any product using oil, natural gas, natural gas liquids, hydrocarbon products or hydrocarbons as a raw material or component; or

3. Any activity authorized by a lease issued under the Indian Mineral Leasing Act of 1938, 25 U.S.C. Sect. 396a-396g or by a contract entered into by the Nation under the Indian Mineral Development Act of 1952, 25 U.S.C. Sect. 2102-2108.

[44] Montana v. Blackfeet Tribe of Indians, 471 U.S. 759, 764 (1985).[45] 25 U.S.C. §5201

[46] Cotton Petroleum Corp. v. New Mexico, 490 U.S. 163 (1989).

[47] A list of Tribal Compacts and Agreements with the State of Oklahoma filed with the Oklahoma Secretary of State is available online at https://www.sos.ok.gov/gov/tribal.aspx (last accessed July 14, 2020).

[48] Merrion V. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130, 137-38 (1982), citing Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation, 447 U.S. 134 (1980).

[49] Id. at 135. The Court also noted the required approval of the Secretary of the Interior as an additional constraint. The Tribe’s constitution authorized its tribal council to enact ordinances levying taxes on non-members of the tribe doing business on the reservation “subject to approval by the Secretary of the Interior.” At the time, the Jicarilla Apache Tribe, which was organized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, was still operating under its Revised Constitution adopted by the Tribe in 1968 (approved by the Secretary of the Interior in 1969). As with many form tribal constitutions provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to tribes organized under the IRA, the Tribe’s constitution continued to subject its tribal ordinances to approval.

[50] Kerr-McGee Corp. v. Navajo Tribe of Indians, 471 U.S. 195 (1985). Unlike the Jicarilla Apache Tribe, the Navajo Tribe had not elected to organize under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

[51] See, e.g., Atkinson Trading v. Shirley, 532 U.S. 645 (2001).

[52] For further discussion on this topic, see generally Taiawagi Helton, Indian Reserved Water Rights in the Dual-System State of Oklahoma, 33 Tulsa L.J. 979, 994-96 (1998); Robert T. Anderson, Water Rights, Water Quality, and Regulatory Jurisdiction in Indian County, 34 Stan. Envtl. L.J. 195 (2015); Joel West Williams, The Five Civilized Tribes’ Treaty Rights to Water Quality and Mechanisms of Enforcement, 25 N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J. 269 (2017).

[53] See generally Helton, supra, at 994-96 (analyzing the Five Tribes Water Doctrine as one basis for Indian water rights in Oklahoma)

[54] See generally Winters v. United States, 207 U.S. 564 (1908).

[55] Cappaert v. United States, 426 U.S. 128 (1976).

[56] See Williams, supra at 291-96 (noting that federal courts have not yet directly confronted the question of whether federal reserved water rights include implied rights to water quality and analyzing the issue).

[57] Montana, 450 U.S. at 550-554.

[58] Id. at 554.

[59] Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma, 397 U.S. 620 (1970).

[60] Montana, 450 U.S. at 555, n. 5. (“Neither the special historical origins of the Choctaw and Cherokee treaties nor the crucial provisions granting Indian lands in fee simple and promising freedom from state jurisdiction in those treaties have any counterparts in the terms and circumstances of the Crow treaties of 1851 and 1868.”).

[61] See Anderson, supra at 215-16.

[62] City of Albuquerque v. Browner, 97 F.3d 415, 423 (10th Cir. 1996).

[63] Pub. L. No. 109-59, 119 Stat. 1144 (2005) at § 10211.